THE TOXIC TIME BOMB IN SKINCARE PRODUCTS:

MICROPLASTICS & MICROBEADS

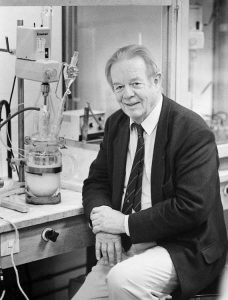

In 1978, in a quiet laboratory at the Norwegian Institute of Technology in Trondheim, the late Professor John Ugelstad did something amazing that was only previously achieved by NASA. The Americans claimed that we would need the weightless environment of space but John Ugelstad managed to produce it on earth – perfectly spherical microscopic particles of plastic.

Why go into space when you can go to Trondheim?” asked Newsweek once in the 80s.

Professor John Ugelstad in his laboratory at Gløshaugen in Trondheim, where the first of the famous particles saw the light of day in 1978. Photo: SINTEF/Jens Søraa

In the following years, the “Ugelstad spheres” was hailed as a minor medical breakthrough; they could be used for cancer treatment, HIV research and even in areas outside medicine such as spacers in LCD screens.

These plastic microspheres are also an ecological disaster on a scale that is largely incomprehensible.

While the value of these microbeads is undoubtedly invaluable when used in science; the use of microbeads in cosmetics, found in everything from facewash to toothpaste to shampoo to hand wash is having a harmful impact on the natural world. To understand why something so innocuous is causing a destructive impact to marine life, you only have to look back to the invention created by Ugelstad.

Microbeads, by design, get into hard to reach places and it’s this intrinsic property which is the reason trillions of these microscopic pieces of plastic end up in rivers, estuaries, seas and oceans every single minute of every single hour of every single day as no waste water treatment plant can filter out these pollutants.

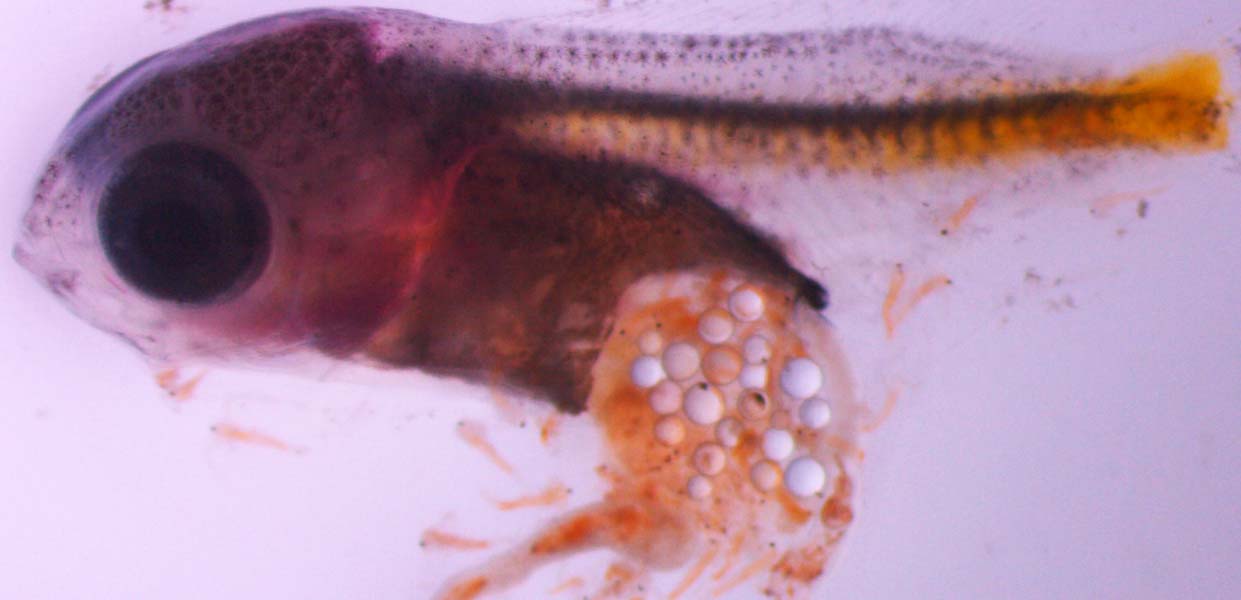

As these microscopic bits of plastic are so small, collectively these microbeads have a huge surface area, allowing it to absorb large quantities of toxins, pesticides & other pollutants. Once in the marine environment, these then become snacks for microscopic plankton; soon enough the big fish eat the little ones, the beads start showing up in the stomachs of larger fish, and filters right through to your dinner plate and inevitably you.

Microplastics found in Damselfish larvae.

A few years ago it wouldn’t be uncommon to see packaging triumphantly declaring the presence of cleansing microbeads. What was once a major selling point for refreshing, cleansing cosmetics has now become a byword for environmental disaster.

With the looming threat of the world’s oceans turning into a plastic soup and forecasts of there being more plastic (by weight) in the oceans than fish by 2050, the Netherlands was the first country to ban microbeads in 2014. Shortly followed by Austria, Luxembourg, Belgium and Sweden in issuing a joint statement to EU environment ministers calling for an EU-wide ban on microbeads.

The UK, while a little late to the party banned the manufacturing of microbeads from January 2017, a major win for the hard working people across multiple organisations such as Greenpeace, Ellen MacArthur Foundation and more.

With the laws invariably banning the use of microbeads, large multinational corporations have taken action too. Unilever said it would stop using microbeads in 2012 and has since completed its phase-out; Procter and Gamble said it was “on track” to remove all plastic microbeads from its products by the end of 2017; L’Oreal and Johnson & Johnson has a similar timescale.

This is something that we should all celebrate, as we move towards a future that is more ecologically secure but sadly even though all the research has shown the ecological devastation plastics in the environment can cause, there are plenty of skincare products which still contain microplastics.

The distinction between microbeads and microplastics is important, but the problem they cause is ultimately the same. Microbeads have been used in cosmetics for its ability as an exfoliator. Microplastics which are usually smaller is not used for any functional reason. It is used for nothing more than for aesthetic purposes – to give a sheen to the product.

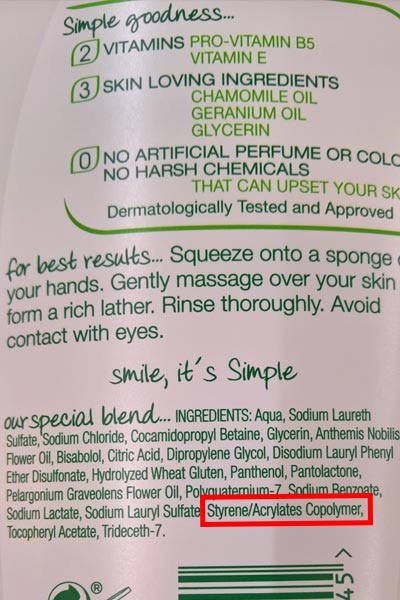

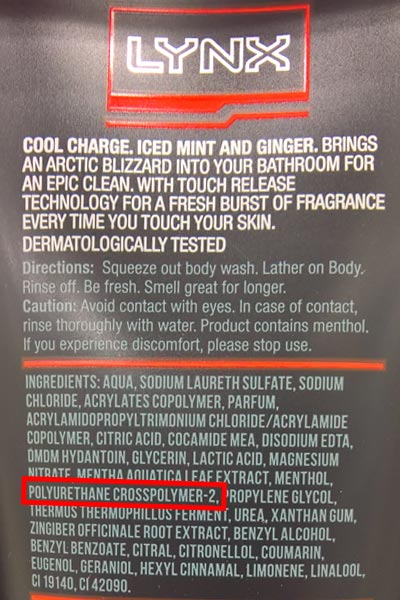

Microplastics added to skincare products for aesthetic purposes.

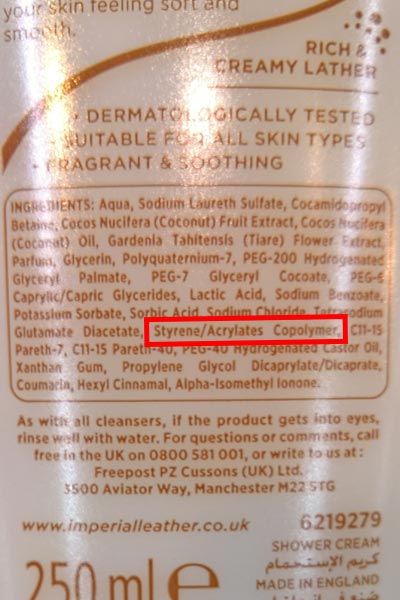

The United Nations Environment Programme (Plastic in cosmetics – 2015) & The European Commission (Intentionally added microplastics in products – 2017) have both identified Styrene/Acrylates Copolymer, a copolymer of styrene and methacrylic acid with a typical particle size of just 0.18μm, as a microplastic, it possesses the typical properties of plastic. It remains as a solid in water and the biodegradability is limited, which is polluting the environment – last August, the results of a study by Plymouth University caused a stir when it was reported that plastic was found in a third of UK-caught fish, including cod, haddock, mackerel and shellfish.

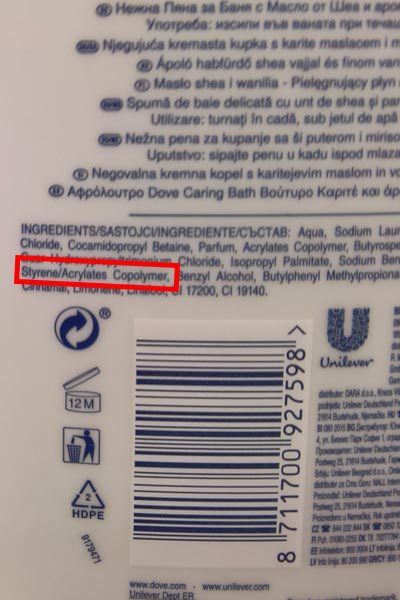

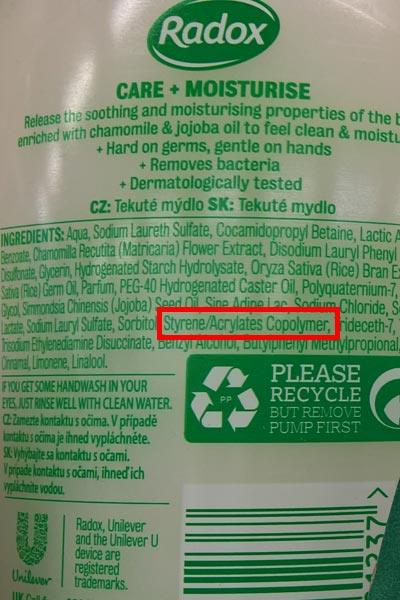

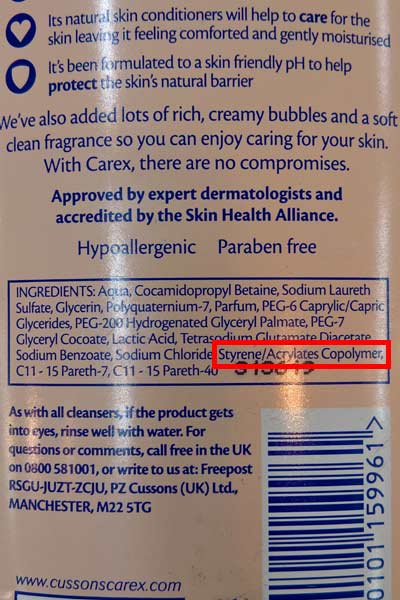

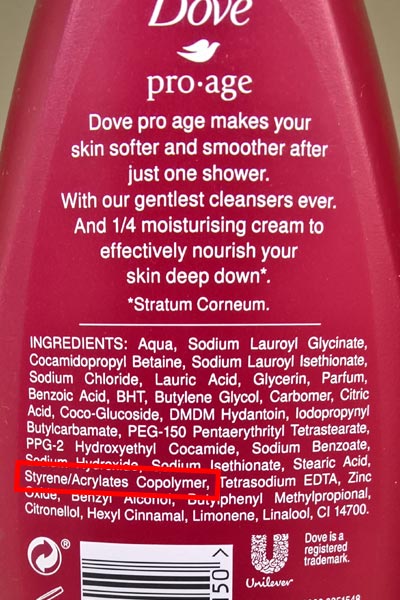

Just a short stroll down the toiletries aisle at the local supermarket shows how widespread the issue is, with numerous products containing the offending microplastic which is polluting our environment.

Simple

Lynx

Dove

Radox

Carex

Palmolive

Dove

Imperial Leather

Using the chemical manufacturer’s data on Styrene/Acrylates Copolymer, of which 40% is composed of the solid plastic. With up to 1% recommended usage, in an average 200ml bottle, this means you can have up to 0.8 grams of plastic.

As we know the diameter of the microplastics at 18μm, about double the size of a bacterial cell, we can work out the exact weight of each micro particle piece of plastic with the density at 1.03 G/Ml using the formula m=pV. Plugging the numbers into the equation, each microplastic particle weighs an astonishing 0.0000000314524 grams.

With up to 0.8 grams in each 200g bottle, there is a worrying 254 million particles of tiny plastic in each bottle, with each particle having the capability of mistaken as food by many invertebrate organisms, i.e. those lower down the food-chain which usually serving as prey for higher organisms as shown in a study by Ward and Shumway (2004).

The scale of the tiny problem is huge. The size, surface area and sheer number, makes microplastics a huge problem once they make it into marine ecosystems.

Whilst we applaud the corporations that have taken the step towards a more sustainable future, the resilience to remove microplastics is deeply concerning.

It doesn’t have to be this way, we can make a positive change to the health of marine life by simply reading the ingredients.

It’s up to us to take care of the world, just as the world takes care of us.

Leave A Comment